By Tashi McQueen AFRO Political Writer

For more than 100 years, Black Americans have been seeking reparations as compensation for centuries of free, Black labor. And while most are familiar with the 1865 initiative that gave slaves “forty acres and a mule,” what they might not know is that slave owners along the South Carolina and Georgia coasts received their land back the same year– and they had federal help to do it.

According to the Pew Research Center, though the “forty acres and a mule” initiative had promise, it was completely reversed mere months after it went into effect. Slave owners could take their land back from the slaves who had just received it as reparations if they simply appealed directly to President Andrew Johnson, the Southern sympathizer in charge after an assassin’s bullet took the life of Abraham Lincoln.

In fact when it comes to compensation for the chattel slavery that ended in 1863, America has already paid reparations– to the slave owners of the day.

According to information released by the U.S. Senate on the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, shortly after the emancipation of their slaves, owners were paid monetary damages for their losses. The funds paid out during this time were used to pay off debts, purchase land, build houses and undoubtedly push the White race and its future generations forward in any way the former slave owners saw fit.

“Originally sponsored by Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, the act freed slaves in the District of Columbia and compensated owners up to $300 for each freeperson,” reads information from the U.S. Senate.

Meanwhile, former slaves struggled to make the most of their “freedom” in a country that soon developed new forms of oppression. With the death and inadequate funding of programs meant to get Black folk on their feet after the back-breaking ordeal of chattel slavery, reparations for the first few generations of freed slaves and their descendants eventually fell to the wayside.

Over the years, African Americans may not have received true compensation for the atrocities they and their ancestors endured– but multiple groups of people in the United States have. Past success regarding reparations has proven that the country is absolutely capable of providing monetary compensation for wrongdoing against a specific group of people on a national scale.

“Native Americans [received reparations] beginning in 1924 with the Pueblo Lands Act of 1924,” said Allen Davis of Racial Justice Rising. “Congress authorized the establishment of the pebble lands board — they allocated $1.3 million to the Pueblo for land that was taken from them.”

“In 1950, the Navajo Hopi Rehabilitation Act was passed, authorizing an appropriation of $88 million over 10 years,” Davis continued. “The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, gave $1.2 billion or $20,000 per person an apology to each of the approximately 60,000 Living Japanese Americans who in turn during World War II.”

According to Davis’ research, though Black people have not received reparations as a whole, there was one African-American man who received reparations for his slave labor.

“[In] 1773, one African-American person who was formerly enslaved received reparations,” said Davis. That year, a Black man and former slave named Caesar Hendrick received $23 in damages and costs from slave owner Richard Greenleaf.

It was the earliest case Davis found concerning the rights of enslaved people and reparations in the U.S. Following his win, there were others.

Henrietta Wood was already a free woman when Sherriff Zebulon Ward abducted her and sold her into slavery in 1853, according to information provided by the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center. She ended up toiling under the hot Mississippi sun for more than a decade, while Ward went on to join the state legislature of Kentucky.

When her owner heard that the Civil War was coming to an end– and he was on the losing side–he moved to Texas, where information and the liberation of slaves was slow to arrive in an age without internet or social media.

Despite attempts to conceal the truth about the Black liberation, Juneteenth arrived anyway.

Today, descendants of Black slaves are demanding monetary compensation for the work their ancestors put into building one of the greatest countries in the world.

Legislation and reparations

The first notable federal attempt for enslavement reparations was in 1989.

Rep. John Conyers, (D-MI-01) introduced bill H.R. 3745, the Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African-Americans Act in 1989. The bill aimed to examine the impacts of slavery and discrimination, look at lingering negative effects on African Americans and recommend appropriate remedies.

It died in the congressional House judiciary committee in 1990, according to Congress.gov.

In 2021, the attempt was renewed by Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, (D-TX-18), and co-sponsored by 184 more House Democrats with bill H.R. 40. The House committee recommended the advancement of the bill, but it has not passed the House yet.

Though federal government reparations initiatives for African Americans have not been successful, in recent years at the state level, some have.

California was the first state to authorize the study of reparations in 2020.

“The task force was established to identify the harms experienced by African Americans from the period of enslavement to the present,” said Cheryl Grills, of the California Reparations Task Force (CRTF).

CRTF is operated by the California Department of Justice.

“The task force was charged with understanding the costs associated with those harms, crafting an apology, coming up with ways to calculate the cost of those harms and making other kinds of recommendations that would allow us to be in alignment with the United Nations conditions that must be met,” said Grills. “Things like satisfaction, compensation, restitution, guarantees, non-repetition and rehabilitation.”

Grills said on June 29, the California legislature will be presented with a final report of over 115 recommendations.

Grills said recommendations include expanding access to career technical education and implementing systematic reviews of school discipline data across schools in the state. Reducing the placement of Black children in foster care and increasing kinship placement for Black children is also a priority, along with ensuring incarcerated people receive adequate pay for their labor within jail.

“The hardest work is ahead of us,” said Grills. “[We must] monitor and track what the legislature and the governor’s office does with our recommendations. That’s going to require a lot of ongoing community engagement on the issue of reparations and amassing and strategically engaging allies.”

Reparations work in Baltimore

At the 2023 State of the Black World, held in Baltimore, reparations nationally and globally were a central discussion point. But while some are seeking reparations for chattel slavery, others are seeking compensation for the harms done to the Black community as a result of the “War on Drugs” and all that it entailed– including the mass incarceration of African-American men, women and children.

The city is close to getting its own reparations commission for those impacted by the criminalization of drugs.

“It’s exciting to see that the city council is in the direction to really understand and put together a commission to understand the impact and specifically the economic impact of the reparations on the city and for the citizens of Baltimore,” said Joshua Harris, vice president of the Baltimore NAACP.

The Community Reinvestment and Reparations Commission bill 23-0353 was approved by Nick Mosby, city council president, on May 15 and now awaits Mayor Brandon M. Scott’s signature.

“I am confident this bill will go into law as soon as possible,” said Mosby, in a statement.

According to the bill, the commission will disburse the city’s portion of the state’s community reinvestment and repair fund. Funding will go to community-based organizations supporting low-income communities. Money would also be used to address the effects of unequal enforcement of cannabis law that took place before July 1, 2022.

“Where and how do we spend that tax revenue?” asked Harris, addressing important questions surrounding all reparations debates. “How can we make sure the commission has an opportunity to determine the best places to spend that tax revenue– and ensure there’s repair for the harms caused by the war on drugs?”

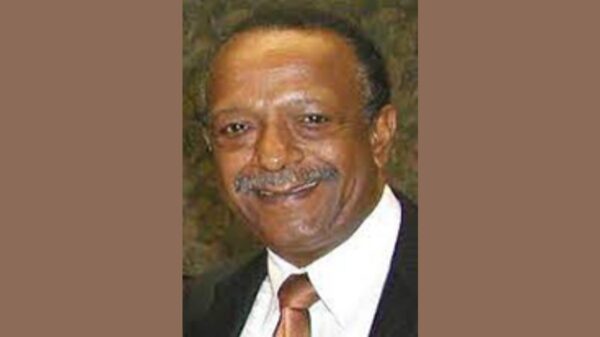

Kamm Howard, executive director of Reparations United, spoke with the AFRO about the issue.

“No matter where a person lives, the global reality right now is built on centuries of crimes and those crimes continue to impact the world,” said Howard, who believes community members must begin the movement when it comes to solutions.

“You’re going to get the government to act on this,” said Howard, speaking directly to residents about the strength of voters banding together. “The community acts as if it comes from the bottom. Our job has always been to educate legislators about reparations.”

Though the pandemic was a time of tragic loss and devastation, activists said the funding made available to offset the effects of the pandemic proves the country is capable of paying what it owes to the descendants of chattel slavery and those affected by decades of Jim Crow, redlining and countless other racist policies.

Davis said he believes the federal government is truly responsible for necessary reparations for African Americans.

“The only entity that can provide anything close to justice is the federal government,” said Davis. “As we saw during COVID-19, suddenly the federal government created trillions. The federal government has the money.”

Tashi McQueen is a Report For America Corps Member.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login